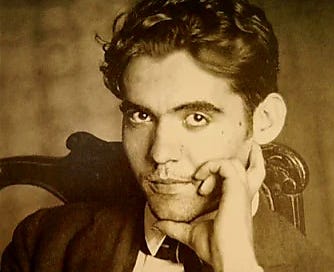

The poet and playwright Federico García Lorca was executed in 1936. He was just thirty-eight years old.

Until a few weeks before his death, Lorca was living in Madrid, but then the Spanish Civil War broke out, and, ignoring his friends’ advice, he moved back to his family’s home just outside Granada.

This turned out to be a terrible mistake.

Nationalist troops quickly took control of whole swathes of southern Spain and, having previously voiced his support for the Republicans, Lorca was soon arrested and shot.

Like so many other victims of the war, his body was buried in a makeshift grave that will probably never be found.

I’ve recently begun work on a new novel that swings between a modern narrative and a dramatisation of the last few years of Lorca’s life.

When writing about Lorca it’s impossible to ignore his death. However hard you try to bracket it out, it perpetually hovers around like the birds circling the corpses in his poems and the grief-stricken characters haunting his plays.

One of the most tragic aspects of Lorca’s short life was the fact that, having struggled for years to find his voice and make a name for himself, he died just as he was beginning to enjoy the freedom and acclaim he so deserved.

There are also disturbing parallels between Lorca’s life and his work. As if possessing a foreknowledge of his own death, his tragic poems and plays (e.g. the goring to death of the bullfighter in Lament for Ignacio Sánchez and the deaths of the bridegroom and bride’s lover in Blood Wedding) mirror his violent destiny.

When you study Lorca’s biography things get even spookier.

Not long before his arrest and execution, he was paralysed by a sense of foreboding after witnessing a group of wild boar attack and kill a lamb. And he was a tireless entertainer – a gifted pianist, a raconteur, the life and soul of the party – but during impromptu performances would often jokingly act out his own death.

Helen Grant met Lorca in Oxford when she was a student and he briefly visited the UK on his way to New York. Although struck by his playful charisma, she noted that, in quieter moments, his eyes revealed something very different – ‘an elemental sorrow for the nature of things’.

It would, though, be wrong to characterise Lorca’s poems and plays as inherently morbid or depressing.

The way his work juxtaposes desire, death, and the transcendent power of nature is life-affirming. It wakes us up.

Like a wrathful angel’s disarming song, it reconnects us to our emotions, and reminds us to recognise the preciousness of life - to value every moment we’re alive.

James Lee © 2023