Ghostly Radiance: Paintings from Picasso’s Blue Period

"The radiant figures in silent meditation, or drifting around like angelic spirits, mirror everyday states of mind – those moments of lucid melancholy that are part of the ebb and flow of human life."

Picasso was an extraordinarily versatile and prolific artist.

Many people think about him as a Cubist, but, in reality, the focus and style of his art evolved over time.

His oeuvre is often split into distinct phases (Primitivism, Cubism, Neo-Classicism, Expressionism etc).

All of these phases are fascinating, but the one that has always intrigued me most is his Blue Period (1901-1904).

At this time, Picasso was an ambitious young artist.

He was in his early-twenties, living near Montmartre, and trying to make a name for himself in Paris.

His determination to be accepted by the Parisian art world is evident in the way he constantly referenced acclaimed artists in his own paintings.

For example, the poster on the wall above the bed in The Blue Room is an artwork by Toulouse-Lautrec; and the posture of the female figure mimics drawings by Degas, and statues by Rodin.

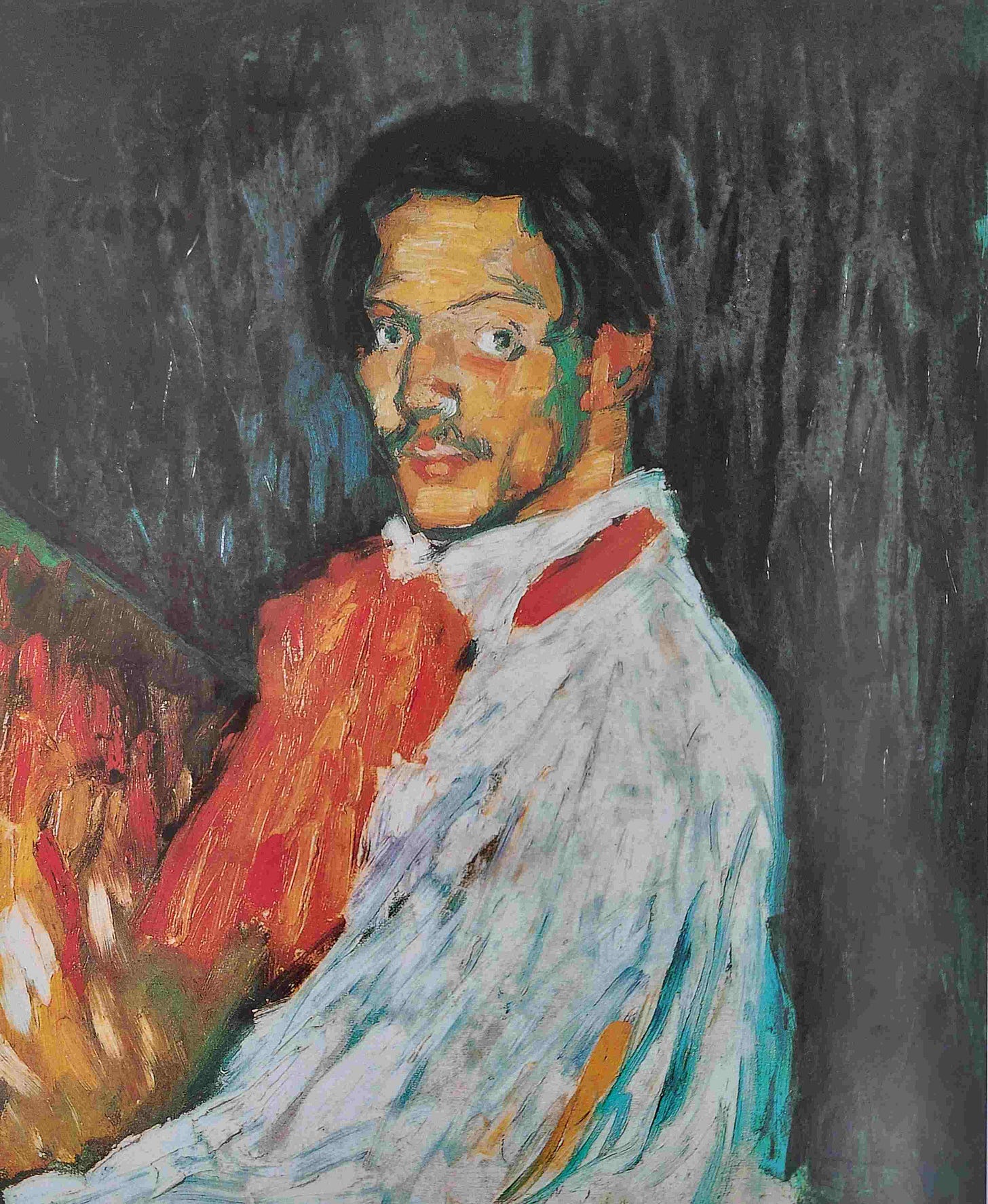

Picasso’s level of self-belief is also evident in his self-portrait Yo Picasso (a title that could roughly be translated as: ‘I am the great Picasso! A genius! And about to take the art world by storm!”)

Although his work caught the eye of dealers, Picasso’s financial situation became increasingly precarious, and, less than a year after arriving in the French capital, he was forced to return to Barcelona.

He made another disastrous attempt to move back to Paris at the end of 1902, but, within months, had to move back to Spain once again.

He even had to sell one of his paintings to his colourist’s wife to pay for his journey home.

Despite these setbacks, Picasso managed to create a deeply evocative and poignant collection of paintings over these 2-3 years.

They can partly be seen as an emotional response to the death of one of his friends, Carles Casagemas - who had committed suicide in early 1901.

But they were also inspired by Picasso’s visits to a women’s prison, Saint-Lazare, in Paris.

Many of the inmates at Saint-Lazare were prostitutes who had been incarcerated with their young children.

Picasso’s paintings of these women are weirdly arresting.

The way that the melancholic blues of their clothes, and bluish-greys of their prison cells, contrast with the radiant luminosity of their skin generates a sense of pathos; and portrays them as angelic – as saints or Madonnas.

But the emotional atmosphere transmitted by these artworks is also highly romanticised.

As the art historian John Richardson has pointed out, they are connected “far more to the etherealised melancholy of modernisme than to the grim realities of prison”.

If these paintings can so easily be characterised as patronising and voyeuristic, why do they continue to fascinate people?

This might, in part, be because they express something essential about the human condition.

The radiant figures in silent meditation, or drifting around like angelic spirits, mirror everyday states of mind – those moments of lucid melancholy that are part of the ebb and flow of human life.

Of all the paintings that Picasso created during his Blue Period, my favourite is the enigmatic masterpiece La Vie.

Painted in 1903, it depicts a naked young couple standing beside a clothed mother who is holding a sleeping baby in her arms.

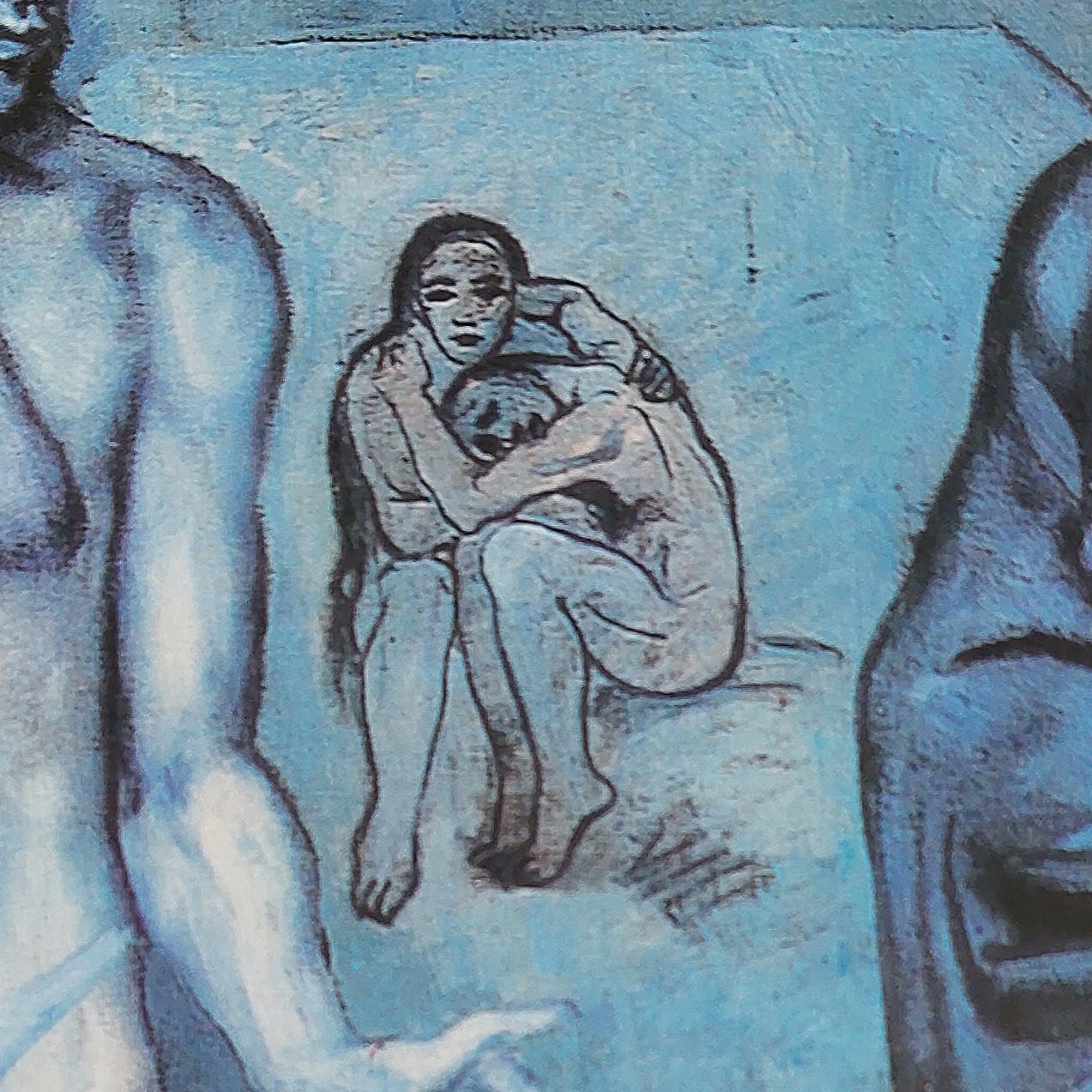

Behind these four characters, there is an arresting painting of two naked and forlorn figures locked in an embrace.

And below this painting is another of a naked figure with his head bowed and his body curled up in a foetal position.

I love the mysteriously intimate atmosphere of this whole image.

The male figure at the forefront of the composition is a depiction of Picasso’s friend Carles Casagemas (the one who had committed suicide two years before), and the woman is a depiction of his girlfriend, Germaine.

Casagemas was supposedly impotent, so, by placing him and Germaine next to a mother and young child, Picasso might have wanted to express something about ‘impotence’ and ‘fertility’.

Or maybe, like other Blue Period paintings that feature Casagemas, it was cathartic - part of a broader attempt to come to terms with his friend’s death?

Or are these figures symbols/metaphors for something else?

Interestingly, x-rays have shown that Picasso originally painted an image of himself beneath the space where he later painted Casagemas.

And the distinct way that the male figure is pointing his index finger at the mother mirrors depictions of the Magician on 19th Century tarot cards.

Then there’s the arresting painting of the forlorn couple in the background.

They remind me of depictions of Adam and Eve - of couples expelled from paradise - and especially of Edward Burne-Jones’s painting Love Among the Ruins.

So, what is going on in La Vie?

What does it mean - what, if anything, was Picasso trying to communicate?

Art historians have argued about this for years.

The truth is that, like so many of Picasso’s artworks, it’s a mystery – a riddle that’s endlessly inspiring, but will never be solved.

If you would like to learn more about Picasso’s early life then read Volume I (1881-1906) of the acclaimed and meticulously researched biography A Life of Picasso by John Richardson.

“Lucid melancholy.” Yes. I feel fortunate to have seen most of these up close. The posthumous portrait of Carlos is a heartbreaker. We don’t usually associate Picasso with pathos (at least, I don’t) because much of his work is intellectually driven. Tge blue period reveals his tender side.

Wonderful, James! Some of these paintings are new to me, including La Vie which I find very powerful. Thank you!